The city is known as the starting point for renowned trekking destinations in the Annapurna Region. Before the pandemic, nearly 1,600 guides and porters were employed by 165 trekking agencies to serve tourists. However, about 50 percent of them have left their jobs due to low pay during the pandemic. About a quarter of trekking agencies have also shut down due to the pandemic. Many have gone abroad for jobs, while some have shifted to agricultural works or started private businesses.

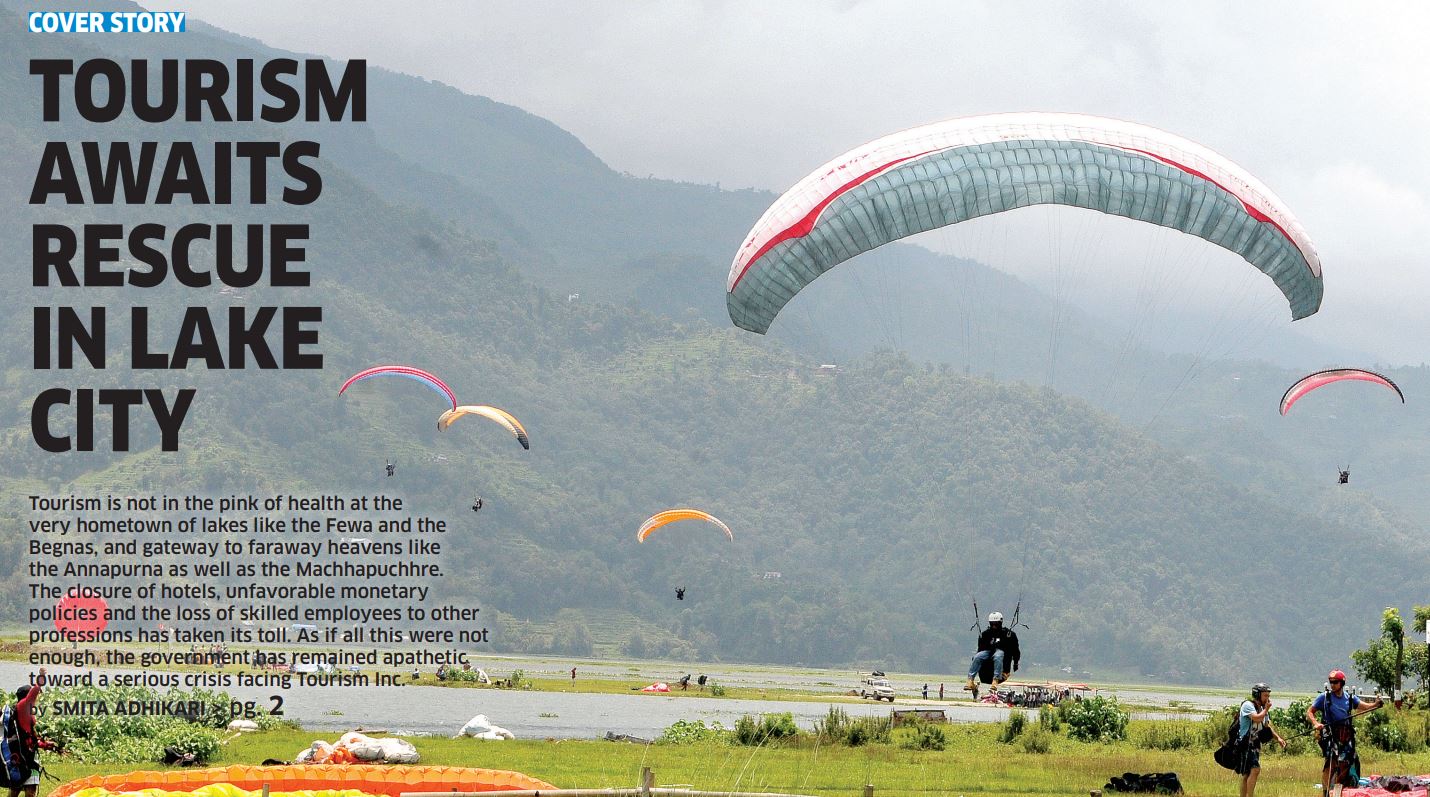

Krishna Acharya, vice-president of the Trekking Agents Association of Nepal (TAAN), Gandaki Province, said it would be challenging to operate groups in trekking areas once tourists start coming. To recover from this problem, TAAN has initiated efforts to produce more trekking guides by providing training to newcomers. But these efforts have not been successful due to policy difficulties in technical education and vocational training, he added. As umbrella organizations of businesses, associations like TAAN are unable to manage resources for post-pandemic recovery programs. The reason is that they are already suffering from financial losses and dealing with their own private loans. Almost all tourism stakeholders in Pokhara are similarly unable to take action to recover from the pandemic on their own. The hotel industry is another key indicator of the post-pandemic tourism status of Pokhara. There were almost 1,500 hotels in the Pokhara valley, including the Lakeside area, about half of them registered. Approximately 20 percent of these hotels did not renew after the pandemic and were displaced from the business due to the pandemic-caused financial turmoil. Laxman Subedi, president of Western Regional Hotel Association, says more than half of the hotels in Pokhara are run using bank loans. “However, the monetary policy for loans has remained unchanged since the pandemic and interest rates have doubled. This is causing even established hotels to close.” About 60 percent of hotel employees have lost their jobs, while 30 percent have left the country for employment, stakeholders say. The hotel association too is planning to produce more skilled employees. “But there is a need to lobby hard for lowering bank rates first,” Subedi said. Hotel professionals have not been heard by the government despite frequent demands to make (issuance of) bank loans more convenient for tourism entrepreneurs, according to Subedi. Similarly, records at Nepal Association for Tours and Travel Agencies (NATTA) Gandaki Province show about 25 percent of travel agencies in the Pokhara valley have shut down due to the pandemic. The organization is currently seeking collaboration with government or non-government partners to develop innovative packages for domestic tourists. "The covid pandemic has taught us not to rely solely on the arrival of foreign tourists. That is why we are focusing on domestic tourists while preparing travel packages," Hari Ram Adhikari, president of NATTA Gandaki Province, said. On the other hand, the future of paragliding—one of the major pull factors in Pokhara—is becoming uncertain as operators struggle to find suitable ‘take-off’ points after the Pokhara International Airport started operation. The government has told paragliding operators to move to new locations for safety reasons. Madhav Tiwari, an established paragliding pilot and former secretary of Nepal Air Sports Association, said: "We have been asked to relocate take-off points to facilitate smooth operation of the airport. But they are asking us to do that using our own resources.”