“The reason that doesn’t happen often is because people let it slide. Nobody complains. If they do, the accused will be investigated and action taken,” says Baniya. People must report arbitrary market pricing, should they come across it. That, he says, is the only way to regulate and control the market. Businesses like Mint Brand Collective get away with duping customers because of loose monitoring as well as lack of information.

A few Nepali celebrities promote Mint Brand Collective as a one-stop solution for branded items like Zara, H&M, Coach, Michael Kors and Kate Spade, to name a few. Baniya says this kind of marketing creates a sense of trust among the public. They think if it’s endorsed by their favorite model, singer, or actor, then the place or service must be good. “If a business is cheating its customers, celebrities should have the moral compass not to promote it. It’s their responsibility as influencers,” says Baniya.

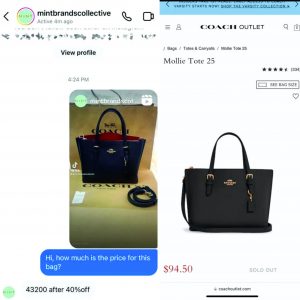

[caption id="attachment_29127" align="alignnone" width="300"] Mint Brand Collective asked for Rs 43,200 for this Coach handbag (left). The price of the

Mint Brand Collective asked for Rs 43,200 for this Coach handbag (left). The price of the

bag, as listed on the brand’s website, is $94.50 (Rs 11,995 at August 16 exchange rate).[/caption]

The Consumer Protection Act 2018 ensures the constitutional right of every citizen to quality goods and services. They can file a lawsuit when that right is violated and be compensated for it. The act also has provisions for fines and punishments. People ApEx spoke to were aware of consumer rights. What most didn’t know was that they could lodge a complaint at the Forum of Protection of Consumer Rights Nepal, or report the offense at Hello Sarkar. Many also didn’t want to ‘go through the hassle’, choosing to warn their family and friends of a ‘bad business’ and leave it at that.

Kumari Kharel, advocate, says most consumer rights complaints are related to expired food or medical issues. There aren’t many reports of exorbitantly priced luxury items. She believes this is why new businesses selling imported brands are cropping up every day. It’s their way of making easy money and they think they can get away with it. “But when customers start reporting these cases, the concerned government body will look into it. As it is, this issue has already caught the authorities’ attention,” says the advocate.

Social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok have also made it convenient for anyone and everyone to run a business. While that has its pros like low overhead cost and a chance to hone your entrepreneurial skills, there are plenty of downsides too—and it’s usually the customer who pays the price. These businesses slip under the legal radar. It’s difficult to monitor them as there is no record of their existence. They also don’t provide a VAT bill and often you can’t return or exchange an item.

According to advocate Kharel, there are laws to punish violators of consumer rights. There just needs to be stricter implementation of those laws. He cites examples of past raids at Bentley, a leather goods store at Durbarmarg, Kathmandu and other similar shops in the area, when customers complained of high prices—some stores had profit margins of as high as 2,300 percent. Kharel says investigators should be sent to different places in the valley for routine checks. If someone cannot provide the procurement invoice for their goods, they should be further investigated.

The Consumer Protection Act 2018 requires the government to establish a consumer court. In February this year, the Supreme Court ordered the government to establish such courts in each of the seven provinces. But there’s still no indication of it being done anytime soon. Activist Baniya says the media can play a crucial role in lobbying for a fast-track system where customers’ grievances are addressed. This, he adds, can instill a sense of fear and thus discipline and ethics in business operators.

Uma Shankar Prasad, an economist and a member of the National Planning Commission (NPC), says selling luxury goods at inflated prices is a market malpractice that the state must look into immediately. As Nepal has banned the import of luxury items and the country is also facing a dollar crunch, we simply can’t afford to let such black markets run rampant.

Rameshwor Khanal, another economist, on the other hand, sees this as a by-product of Nepal not being able to bring international brands or provide good local alternatives. The demand for brands has gone up and businesses are exploiting that, he says.

Many businesses importing branded items evade taxes while bringing and selling luxury goods. The items are usually brought into the country on baggage allowance or through other dubious channels that don’t go through the customs. “This will ultimately take its toll on the state coffers and increase the bigger gap between the haves and the have-nots,” says Prasad.

But all hope is not lost. The issue is being discussed at the NPC as well as the federal cabinet. “Hopefully we can come up with provisions to curb this market malpractice,” he says. In the meanwhile, Baniya urges people to report businesses like Mint Brand Collective so that action can be taken against them. “This will ultimately help regulate the market, make businesses answerable and ethical, and ensure you are getting your money’s worth,” he says.