Quick facts

Born on 25 July 1942 in Sisautiya, Sarlahi

Went to Nandipath Jitu High School, Sonbarsa, India

Graduated from SRK Goenka College, Sitamarhi, India; post-grad from Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu

PhD from Delhi University, India; post-doctoral research on Folklores of Nepal, especially of Mithila from Indiana University, Bloomington, US

Husband of Tara Devi Rakesh

Father to Prabhat Sah, Prashant Sah and Punam Sah

I was born and brought up in a rural village in Sarlahi district. After completing my primary school there, I had to go to India for further studies. There was no high school in Sarlahi at that time.

From an early age, I wanted to be a teacher. So after graduating from India, I began teaching at my village high school, where I went on to work as the headmaster. Incidentally, I had to resign from the headmaster’s position due to constant political meddling.

I then left the teaching job and came to Kathmandu for my master’s degree. After coming to the capital city, I discovered that very few people there knew anything about the Maithili culture. This prompted me to write about it in Nepali newspapers and magazines, starting with Gorkhapatra in 1966.

As far as I can recall, I had no interest in writing before that. I loved teaching and even after coming to Kathmandu, I used to give tuition classes to make some money on the side. Thankfully, my writings on Maithili culture, history and literature were well received.

I was teaching at the Padma Kanya College at the time. I started as an honorary lecturer and got a temporary appointment after nine months. But to become a full lecturer, you had to pass the Public Service Commission’s test. My colleagues and seniors at the college continuously encouraged me to write. The publishers too were kind enough to entertain my writing on their papers. I was given a regular column and they even started paying me. My pieces were also read out on Radio Nepal.

I taught at Padma Kanya for four years before leaving for India for my PhD under the Colombo Plan, a government-sponsored scholarship. When I returned, I was transferred to Kirtipur Campus, where I worked for almost two decades.

I had to change two buses to reach the campus from my house. I did this for 20 years as I never got teacher’s quarters. I was deployed under the government quota, and to be eligible for the quarters you had to be directly employed by the Tribhuvan University.

After years of teaching, I began to lose interest in the profession, which was once my dream career. But I had the option of switching to government administration, and I did.

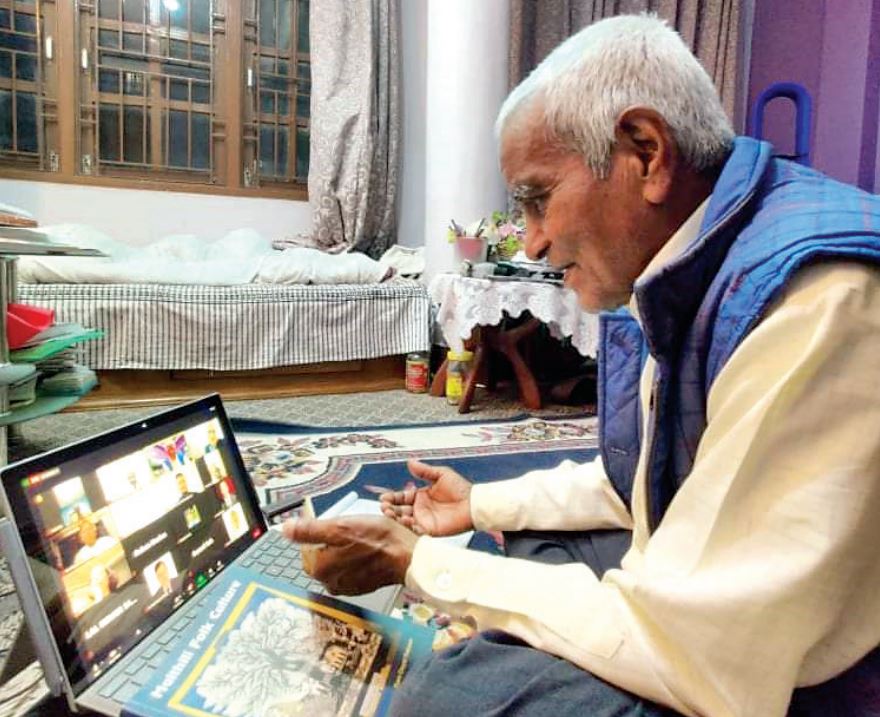

Ram Dayal Rakesh addressing an online event to discuss his book ‘Maithili Folk Culture’.

In 1992, I got appointed as a joint secretary at the Election Commission. For someone who had taught all his life, it was an uncomfortable job. My new colleagues were not particularly fond of me because I was against their spendthrift habits. So they rarely consulted me if something came up. Even the chief election commissioner at the time was unhappy with me. He kept me as a Jageda, a back-up officer. This meant I had only limited facilities and was not allowed to work. All I had to do was sign the attendance sheet.

It was around this time that I got a Fulbright scholarship for my post-doctoral research in Indiana University. I had developed a love for research because I used to do tons of them while writing my columns on Maithili culture and history. As a result, I enjoyed my post-doctoral research work very much.

After returning to Nepal, I served in a couple of government agencies. But I was not going anywhere in my career. I had no chance of getting promoted to the level of government secretary as I had no political connections. So I resigned from government service in early 2000.

I then went on to work with the then Royal Nepal Academy, the National Human Rights Commission, and the erstwhile Other Backward Class Committee. But these jobs too did not last long.

I retired for good in 2006 so that I could focus on my writing and research. But I have not been able to spend as much time as I would like to on these things because of my poor health.

I have written almost 45 books in Nepali, Hindi, Maithili and English. All this would not have been possible without my enduring love for folk culture and literature. I am also heavily indebted to my dear readers, my friends and family for their encouraging words and support.

Thanks to their love, I became the first Nepali recipient of the Premchand Fellowship of Sahitya Academy, India, and Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize, Japan. I was also honored by the Vidhyapati Memorial Prize for my contribution to Maithili folklore.

I write in multiple languages because, that way, writing never gets monotonous. At the same time, I feel that had I focused on one language, my works would have had more heft. Probably my contributions would have been more visible too.

My concern is that while countries like India, Japan and Thailand are doing a lot to promote the Mithila culture, authorities in Nepal are not doing much. Mithila is one of the richest cultures and is closely tied to Nepal’s identity. Our government should thus do more to promote and preserve this culture.

About him

Samir Dahal (Grandson)

I am awed whenever I see my grandfather’s room covered with books and awards. He is an inspiration. He has this unmatched love for folktales, which is only accentuated by his literary acuity and agility. His hunger to read and write is legendary. I aspire to follow in his footsteps.

Chandreshwor Mishra (Friend)

Rakesh ji and I share decades-long friendship. I have known him as a kind person who is always helpful to his colleagues, friends and students. His writings are based on solid ground research. He visits ancient places, collects information from indigenous people and publishes them in a simple form. We will always be in debt to him for his priceless body of work.

Kedar Bhakta Mathema (Friend)

People often become a little pompous when they achieve certain fame. But Rakesh ji is not in that category of people despite his recognition as someone who introduced various dimensions of Nepali folk culture to the world. His works are quoted by numerous international researchers, a rarity among Nepalis. And his legacy continues to get bigger by the day—kudos!

A shorter version of this profile was published in the print edition of The Annapurna Express on August 4.