Nepal’s installed power capacity is expected to exceed 15,000 MW by 2030, according to the Electricity Demand Forecast Report 2017.

By 2040, electricity demand is projected to climb to 82,000 GWh, with a corresponding installed capacity requirement of over 35,000 MW.

Hydropower plants are believed to be Nepal’s most reliable energy-source. In theory, the country can produce 50,000 MW of electricity by harnessing its water resources. But there are challenges galore to turn this theory into practice. For one, cost is a big concern.

Dipak Gyawali, former minister of water resources, says Nepal’s electricity production is three to four times more costly than it is in most other countries. “For instance, Ethiopia started producing electricity without foreign assistance and did it at $800 per kilowatt. In Nepal, we had to fork out $2,500 for the same output,” he says.

Building hydropower plants in Nepal is both challenging and costly because of the country’s difficult hill and mountain topography, often with no road access to the project sites.

“A power plant that takes five years to build elsewhere takes 10 to 15 years in Nepal,” says Gyawali. While technology and expertise have helped reduce both time and cost of building power stations, that is true mostly in the case of storage-type hydropower projects. In Nepal, most hydroelectricity projects are run-of-the-river, which don’t have the desired power storage capacity, or the consistency: During the dry season, electricity production of hydropower stations falls by two-thirds of their peak monsoon-time output.

According to the Department of Electricity Development, Nepal has the electricity generation capacity of 2,094.034 MW, of which 20.18 MW comes from solar sources.

Nepal has set the target of ramping up its clean energy output from 1,400 MW to 1,500 MW by 2030 as part of its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But the achievement of this goal remains doubtful, given the country’s patchy record. Nepal had failed to meet its previous NDC target: to expand renewable energy to 20 percent of its energy-mix by 2020. The share of renewable energy was a mere 3.2 percent in 2019, government data show.

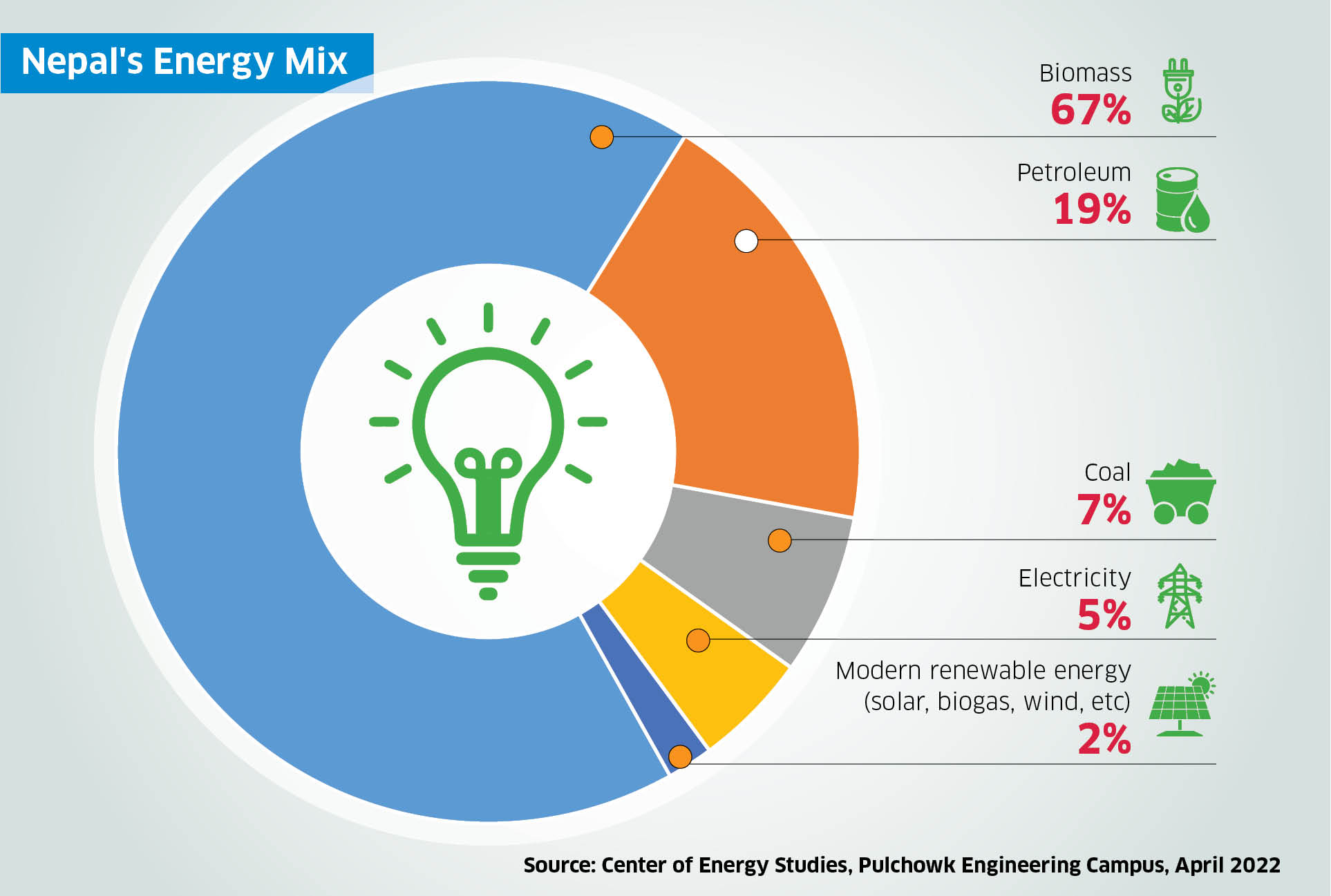

According to a study carried out by the Center of Energy Studies, Pulchowk Engineering Campus, in April 2022, Nepal meets 67 percent of its energy needs from biomass, 19 percent from fossil fuels, seven percent from coal, five percent from electricity, and two percent from alternative sources.

In order to meet the NDC target, say energy experts, Nepal must prioritize clean alternative energy sources alongside hydroelectricity projects.

Solar and biogas technologies could be cheap and viable alternatives, for instance. Solar panels can be set up in each household in a day or two, and approximately a year in case of large-scale production facilities. Likewise, a household biogas system can be installed in two weeks. Madhu Sudan Adhikari, Executive Director of Alternative Energy Promotion Center, believes it is high time Nepal prioritized energy sources other than hydroelectricity to meet its energy needs.

“Generating solar energy is far cheaper than generating hydro energy,” he says. “The cost of building a one MW-capacity hydro plant is around Rs 200m. The same amount of electricity can be generated via solar technology for Rs 70m to Rs 80m.”

But there is a catch. Harnessing the sun’s energy may cost a lot less than generating electricity from water, but solar plants’ power availability factor—a measure of efficiency—of 18 to 20 percent dwarfs that of hydropower stations at 30 to 40 percent. There is invariably a trade-off.

Jagan Nath Shrestha, a solar energy expert, believes both hydro and solar plants can be simultaneously developed, so that energy production does not fluctuate.

Also, finding a large enough area to set up solar panels to support large communities is a big concern, especially in a crowded city like Kathmandu where open spaces are rare.

But this problem also has a solution, says Shrestha. “If, say, 100,000 of the bigger, well-spread houses in Kathmandu valley install solar panels, the surplus electricity they produce can be used to offset any shortfall in the national grid,” he adds.

Better yet, say energy experts, solar technology should work in concert with the biogas systems in rural Nepal where most families still rely on traditional, polluting energy sources like firewood.

It is more costly to install solar panels in individual rural households compared to their installation cost for urban households. But there is plenty of space available in non-urban areas of Nepal to set up small- to medium-size solar facilities to light up small communities. And for biogas systems, they already have easy access to organic materials.

“It takes approximately Rs 100,000 for a household to set up a biogas system for cooking or heating purposes,” says Shekhar Aryal, chairperson of Biogas Sector Partnership-Nepal.

According to Aryal, nearly 1.4m rural households in Nepal have the capacity to produce biogas (at present, only half a million do).

Mass-produced and environmentally-friendly briquettes—compressed blocks of coal dust or renewable products such as paper, sawdust, wood chips and agricultural wastes—can also come handy as many rural areas are inclined towards traditional energy production.

Both hydro and alternative energy sources have their benefits and drawbacks. The goal is not to choose one over the other, suggest energy experts, but to come up with the right mix so as to meet our household and industrial power needs while keeping our environment sufficiently clean.