In the past year or so, the trend of Rohingya and Afghan migrants coming to Nepal through the open border with India has accelerated. This is a delicate humanitarian issue but it is also proving to be a headache for the country’s security agencies who fear unchecked immigration could imperil national security. Moreover, foreign nationals are entering the country not just from Myanmar and Afghanistan.

Countries around the world are caught up in various kinds of conflicts. The likes of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Lebanon, Myanmar, Somalia and Iraq are in the midst of crippling civil wars, leaving thousands dead and countless more homeless and destitute. Desperate, many of them choose to leave their home country.

Even in Nepal, over 17,000 people were killed during the Maoist insurgency and hundreds of families were displaced. Youths started deserting villages; many Nepalis took refuge in other countries.

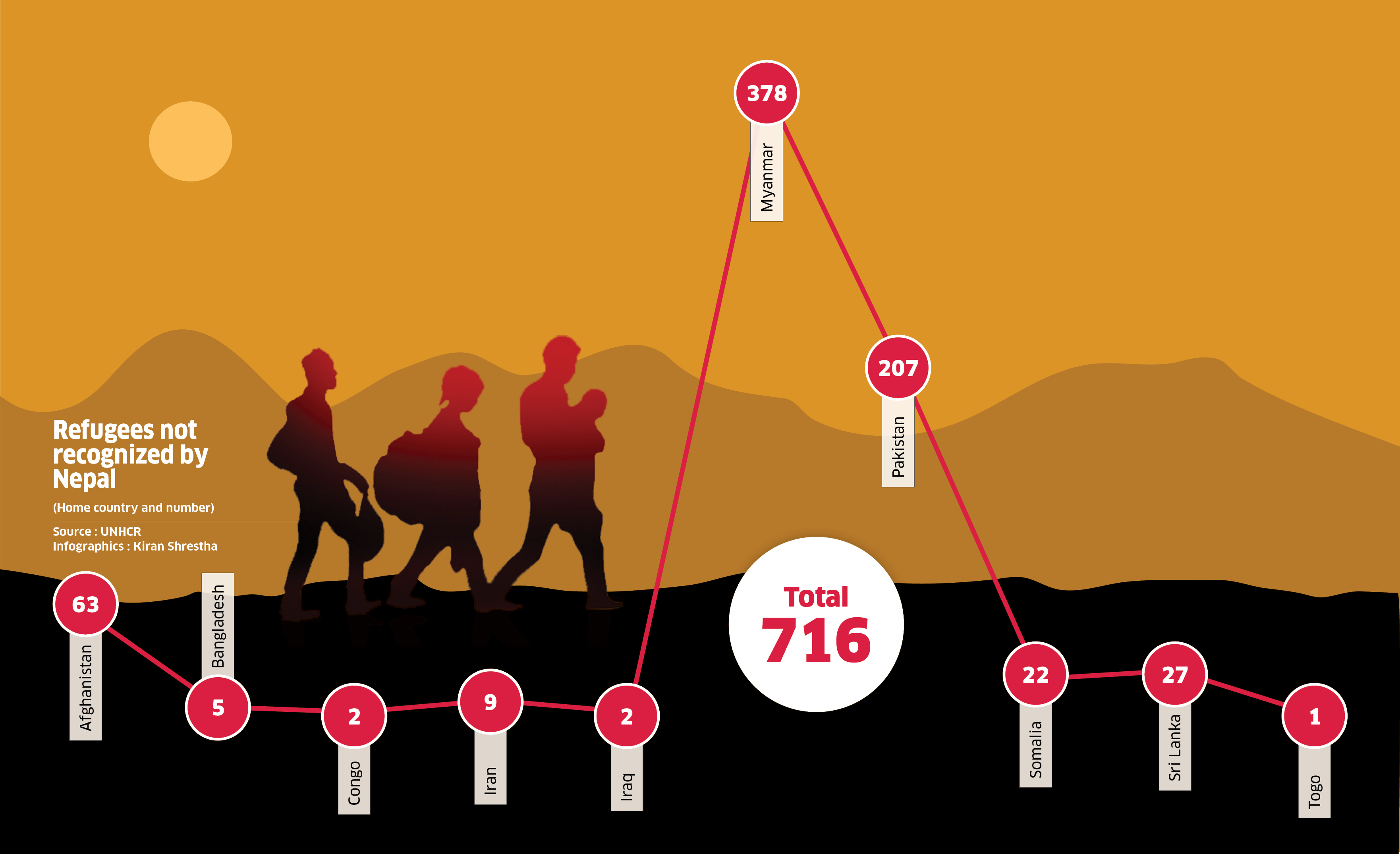

Nepalis have found refuge in the US, Japan, Canada and some European countries. Many have submitted papers certifying the high risk of their return home, making them eligible for residency abroad. The same is the case with 716 nationals from 10 countries—Iran, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Somalia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Iraq, Congo and Togo—who have taken shelter in Nepal. They do not want to go back to their own country but nor can they legally stay in Nepal. Even though the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) lists them as refugees, Nepali laws do not recognize them.

Nepal has instead been treating them as illegal migrants. The country does not recognize refugees from anywhere bar Tibet and Bhutan. Many of these migrants don’t have any papers linking them to their home countries, including their passports. All they have are identification documents issued by the UNHCR, making them liable to get some help from the global body.

Yet even the UNHCR has cut down on the help it was extending to them, with the excuse that the UN headquarters has significantly cut funding following the Covid-19 pandemic and that the bulk of the sum allocated for refugees has had to be diverted in dealing with the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Many of the migrants struggle for two meals a day and yet they opt to stay put in Nepal.

It is relatively easier for people from Myanmar and Bangladesh to seek refuge in Nepal given the open Nepal-India border and the weak presence of the Armed Police Force in border areas. But why do folks from Somalia, Pakistan, Iraq and Congo come here, after long flights and multiple transits? Are human traffickers bringing them to Nepal with the promise of taking them to Europe and America?

No one has clear answers to these questions, neither the government nor the UNHCR.

Just about anyone can enter Nepal on a tourist visa. Our security arrangements at the Tribhuvan International Airport are lax. Due to our unclear immigration policy and connivance of the APF deputed at the border, the number of illegal migrants in Nepal continues to increase. When the Rohingya enter Nepal via India, the AFP does not stop them, and the same is true of Afghans. Police sources speak of many Afghans who have entered Nepal, destroyed their papers and applied for refuge with the UNHCR.

Many of them come to Nepal with dreams of making it to western countries yet not all of them are successful.

In one way, the migrants in Nepal have become stateless. The Rohingya are the most numerous of all migrants in Nepal, followed by Pakistanis (see the table alongside). They struggle on a day-to-day basis. Rohingya, Afghans, Pakistanis and Somalis are often seen protesting in front of the UNHCR Nepal office in Kathmandu, asking for more help to sustain their livelihood.

After they felt that the UNHCR was ignoring them, the Rohingya started entering Nepali villages in search of jobs. Nepali contractors employed them in homebuilding in places like Biratnagar, Kavre and Gorkha. But even the contractors started swindling them when they learned of their illegal status. These foreign nationals are also under constant gaze of security agencies.

The Rohingya mostly live in a camp in Kathmandu’s Kapan while Pakistanis and Afghans are scattered across Chappal Karkhana and Bansbari. Likewise, Somali women mostly live around Lazimpat. A 40-year-old Somali woman said she was thrown out of her flat when she could not pay her rent during the recent Covid-10 lockdown. (Speaking to ApEx, she also confessed to destroying her documents so didn’t have to go back home.) All those listed with the UNHCR do menial jobs.

UNHCR’s role

The UNHCR accepts applications from would-be refugees. It does thorough background checks and rejects applicants with criminal records. The organization issues refugees cards after six months of rigorous investigation. Though listing with the UN body comes with few perks, just being listed makes many feel more secure.

The UNHCR, in cooperation with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), has also been resettling refugees in Nepal in western countries like Canada and Sweden. At the request of the two bodies, the Nepal government has been helping with their third-country resettlement.

But many accuse the UNHCR of negligence in looking after the refugees. It cannot even guarantee their basic needs. Many refugee children have been denied education. Even when they get enrolled in school, they cannot attend online classes as they don’t have computers or smartphones. One Rohingya refugee visited ApEx offices in Teenkune recently, requesting this correspondent to arrange a laptop for his daughter who wants to study online. “The UNHCR doesn’t help us in anyway. Please publish news highlighting our plight,” he requested.

All these incidents suggest that Nepal needs a clear-cut immigration and refugee policy. The current state of ambiguity might be convenient for many but it is not a sustainable—or safe—arrangement.

Deviram Sharma, Former chief, National Investigation Department

A growing security threat

Illegal migration is now a global phenomenon. Geographically and economically big countries might not be burdened much by this problem. In fact, the likes of the US, Australia and France have been accepting many migrants. But for a country like Nepal with a small economy and high unemployment, the entry of migrants might pose a big national security challenge.

If the migrants cannot return to their own countries or be rehabilitated in third countries, there is a risk of them getting involved in illegal activities on Nepali soil. As the government’s oversight is poor, there is also a risk of them being used by certain criminal or terror groups. This is why the entry of foreigners into Nepal must be tightened. We must increase the presence of security forces along the Indian border. It is also important that the Nepal government works with the UNCHR in order to manage illegal migrants. As far as possible, the migrants should be returned to their own country.

Again, Nepal’s economy is weak and unemployment is high. This is precisely why around 10 million Nepalis have ventured out in search of jobs. The government has been unable to give common Nepalis basic facilities like health, education and drinking water. In this condition, can the country afford refugees? In the past, those displaced from Myanmar and India’s Meghalaya had come and stayed here. Even at that time, the government had faced big challenges.

There could soon be a security crisis if Nepal doesn’t reconsider its immigration policies.

Indra Aryal, Human rights and refugee activist

Nepal obligated to act humanely

Nepal is not a signatory to the 1959 UN refugee convention. Nor does the country have domestic laws to regulate refugees. Nonetheless, Nepal gave formal recognition to the refugees from Tibet in 1951 and to the refugees from Bhutan in 1990, in line with the provisions of the same UN convention. But Nepal is yet to recognize the children of these refugees or the entrants into Nepal from these places at other times. The Home Ministry recently decided to recognize the children of resident Bhutanese as refugees but it remains mum in the case of Tibetan children.

When China took over Tibet in 1951, around 23,000 Tibetans had entered Nepal and when Bhutan expelled Nepali-speaking citizens, around 113,000 of them came to Nepal via India. If we add refugees from other countries, there are around 20,000 refugees in Nepal right now.

At different times, those who have felt unsafe in their own country have entered Nepal and the Immigration Department has detained and deported them. But human rights activists have also been successful in stopping many of these human rights violations by knocking on the doors of the Supreme Court. They have successfully freed many detained refugees and stopped their deportation. In these cases, the court has also issued directive orders.

Even though it is not a part of the UN refugee convention, Nepal has accepted the provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), as well as the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984). These provisions have the status of Nepal’s laws, in line with Clause 9 of Nepal’s Treaty Act 1990.

Act 14 (1) of the Universal Declaration and Act 3 of the Convention Against Torture prohibit member countries from deporting those whose human rights are at risk. Also, in lieu of the provisions on self-respect, equality, freedom, legal rights, and rights against torture that are enshrined in Nepal’s constitution, Nepal is bound to give refuge or provide a safe passage to those who rights are threatened in their country.

Nepal treats the refugees in its midst strangely, whereby it allows them to come and yet does not allow them to live in peace.