There is one common motif shared between Buddhist meditation practice and Olympian training: that of the finely tuned lute. Strung too tightly, the strings will break; strung too loosely, the strings will sound off: If the lute strings are too tight, will your lute make a nice sound? If the strings are too loose, will your lute make a nice sound? ... In the same way, if you practice too intensely, it causes stress. If you practice too little, it causes indolence. (Aṅguttara Nikāya 6.55)

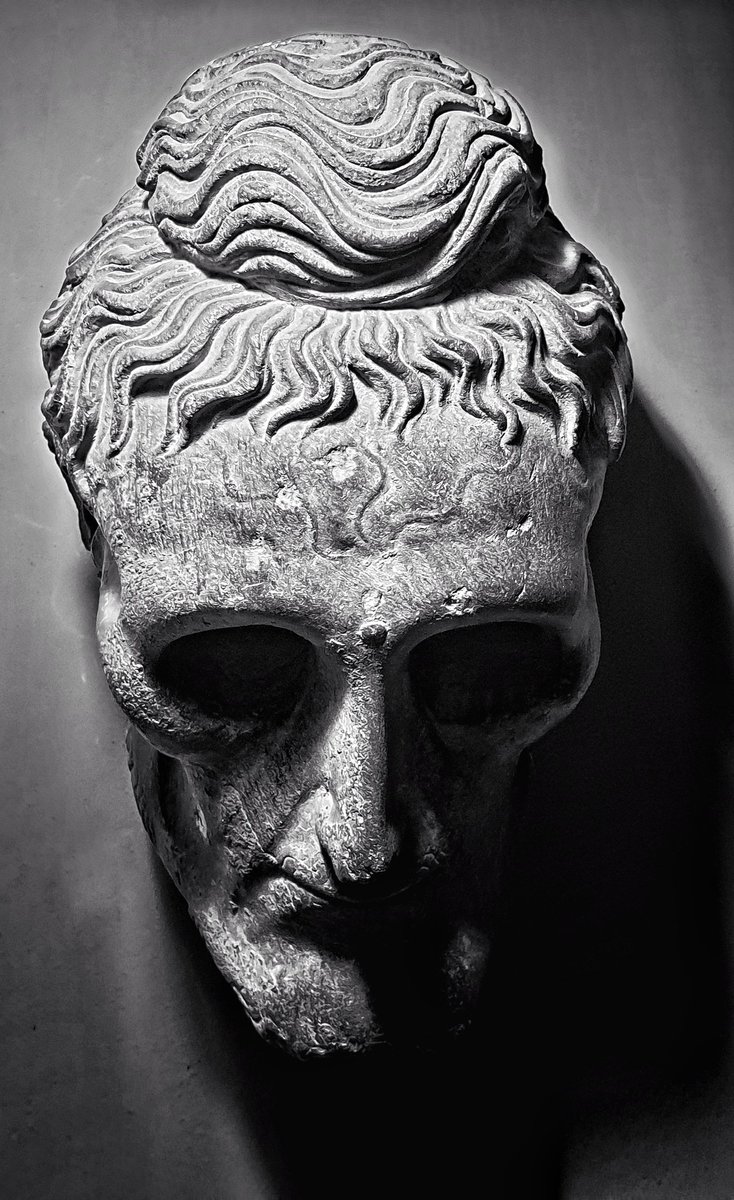

Image of an emaciated Siddhartha Gautama, Gandhara, third century, Peshawar Museum | Twitter

Image of an emaciated Siddhartha Gautama, Gandhara, third century, Peshawar Museum | Twitter

The image of an emaciated Siddhartha Gautama, beautiful yet withered and gaunt, reminds us of two things: first, that any journey, whether to attain enlightenment or become a sporting champion, is inevitably filled with hardship and tribulation. Second, that self-deprivation and forgetting to attend to one’s well-being are no way to accomplish goals.

These ideas are not contradictory. This year’s Olympics in Tokyo have showcased some amazing athletes at the top of their game. One legendary athlete who has not been at the top of her game is Simone Biles, who has come up short at several events. In late July, she withdrew from the women’s finals, citing the need to protect her body and mind after being unable to land satisfactory moves on every apparatus during training.

“I didn’t have a bad performance and quit. I’ve had plenty of bad performances throughout my career and finished competition. I simply got so lost my safety was at risk as well as a team medal,” she declared. “I don’t think you realize how dangerous this is on hard/competition surfaces. Nor do I have to explain why I put my health first. Physical health is mental health.”

While her decision might hurt her team’s chances of winning more gold medals, Biles has brought renewed attention to the long-neglected primacy of mental health. She is far from alone: despite enduring stigma and misconceptions, her withdrawal has resonated with many around the world, feeding into a growing awareness of mental health.

Tennis star Naomi Osaka foreshadowed Biles in many ways, stepping away from press conferences and then from tournaments earlier this year and asserting the need to attend to herself. “It’s OK to not be OK, and it’s OK to talk about it,” she famously wrote for Time magazine after considerable negative media attention. She asserted that fame, publicity, and pressure should not negate the need to “exercise self-care” and “preservation” of mental health.

Some prominent commentators have harshly criticized Biles, hyperbolically accusing her of being selfish, weak, or not a team player. These critics, few of whom are professional sportspeople, have also strongly condemned Osaka in the past, seemingly failing to exercise compassion and remember that sportspeople have valid mental health concerns, just like anyone else.

Like celebrities and politicians, who tend to receive little public sympathy when sharing their emotional difficulties, athletes’ mental health has also been affected by over-the-top judgments. However, there is an increasing generational shift in many countries. Young people seem better than previous generations at recognizing mental health problems.

As mental health awareness becomes more mainstream, there has also been a backlash against what is seen as “coddled” or “spoiled” behavior by those who prioritize personal mental health over traditionally valued goals such as popularity, wealth, or status. Critics assert that Biles made up her mind too quickly without considering her duty to represent her country as an ambassador of American Olympic prowess. However, arguments over whether her call was self-serving, careless, or unpatriotic seem to miss the core point and overlook Biles’ own experience. Not only has she already represented her country estimably for years, the entire point of Biles prioritizing her mental health over more abstract ideals such as national pride or a new gold medal is an affirming statement that there are things in life more valuable than fame, glory, and accomplishment. Someone as accomplished as Biles probably knows this, given the fact that she is already considered by many sports writers and historians to be the greatest gymnast in American history.

Yet we do not need to have reached Biles’ heights of achievement to have valid concerns about our mental health. Even for a perfectly ordinary person with an unremarkable life, there is every reason to be cautious of the narrative that certain goals are necessarily more valuable than others and worth significant sacrifices. We are all familiar with stories of burnout at work, of being so focused on a goal to the point that other demarcations of flourishing are forgotten or left behind. People around the world are discovering, especially post-covid, that mental health and a balance of work or public service and self-care is its own reward or objective, a worthwhile victory in and of itself.

The lesson in the story of Siddhartha’s ascetic phase of extreme self-denial is that he was too focused on his goal, enlightenment, and as a result he hindered himself from actually attaining it. It was only after he accepted nourishment from a humble village girl, Sujata, and left his five ascetic companions, that he could find himself on firmer ground to discover the truth of the cosmos. When the five ascetics found out that Siddhartha was eating and taking care of himself, their disparagement had slight echoes of the criticism directed at Biles, with the future Buddha being accused of cowering away and accepting compromises when he should be laser-focused on his attainments.

Those ascetics later became the Buddha’s earliest disciples at his first sermon in Sarnath, the Turning of the Wheel of Dharma.

Buddhistdorr.net