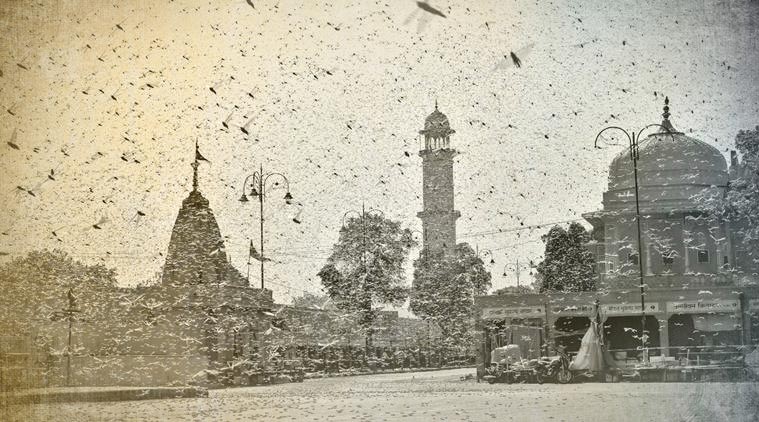

As locusts descended on Gurgaon, India, I watched videos online and realized the area noted for its technological sophistication and prowess looked like an ecological desert. The blue-glassed skyscrapers, asphalted treeless roads, barren streetscapes so different from green rural landscapes of India struck me with their ecological unsoundness. While touted as a “Smart City,” filled with smart people using and selling smart tech, what was most obvious was how helpless the people were in warding off this natural disaster. They had no ducks, no sparrows, no wasps, no schoolchildren picking locusts off the ground to sell to the local government for Rs 25, even. They did not even have soil they could apply with nitrogen fertilizer, another deterrent to locusts.

Yet we’ve been forced to think this way of living is the acme of perfection, one we should all emulate and aspire to. Bill Gates raised $9 billion to create a vaccine for Covid 19. Why did all the nations of the world eagerly handover their health budgets to this tech marketer, instead of banding together to create an international consortium of researchers from universities around the world which they could depend on to deliver for the public good? Why did they believe that the richest man in the world, with many pharmaceutical investments, was the right man for the job?

The trendy term STEM seamlessly fuses science with technology. Science, which has always meant gathering of knowledge through observation, and conclusions based on rational correlations, doesn’t require a techie twin to become science. With the STEM worldview, however, we have started to assume that all of our knowledge depends not on long and thoughtful observation, but on technological machines which define the contemporary scientific encounter. If there’s no machine to contextualize the phenomena, surely it cannot be science!

A few days ago, I had to call a fridge repairman to refill my fridge with hydrocarbon gas. As he stood there among the copper tubes and wires, cutting and fusing things with his blowtorch, filling my kitchen with toxic gases, it occurred to me that this was a futile, convoluted exercise. Who came up with this idea of creating this giant machinery held together with wires, tubes and gases, simply so that people could keep their food cold for a day or two? We were willing to blow a hole through the ozone for this enterprise and kill all of life in the process. What leap of logic made us think that this invention (designed by men who’d never tried to clean a plastic ice-cube tray, for one) had to be in everyone’s kitchen?

The ventilator, which fills people up with oxygen, operates on a similar premise: the body is a big complicated machine, one we must refill with gas when it runs out of it. It is no surprise that the dials with which a fridge repairman fills up a gas chamber is similar to the dials which regulate oxygen in a ventilator. This mechanistic view is a Western way of looking at the body. X-ray, ultrasound and other imaging devices peer into the body to understand its workings. The body is to be repaired by being cut, drilled, blowtorched by chemicals and radiation. We glorify the technology behind these procedures. We are told these apparatuses are the height of scientific thinking, not a rather crude way to approach the complex workings of a body with an unknowable mind.

A recent discussion I got into Twitter with a young woman illustrates this point. A young baby was left tragically deformed by doctors at Grande Hospital after they used suctions to mechanically pull water from his brain. Babies in Nepal are traditionally massaged with mustard oil to avoid this very problem of inflammation and water collecting in the brain. Fenugreek is a known anti-inflammatory agent. The Tamang woman who shaped my nephew’s head did it beautifully. I had sat and watched the way she patted the baby’s head into shape.

Knowing I was straying into sensitive territory, but pushed by the thought of the young child, I made the point that the tragic latrogenic distortion of Rihan’s head could be corrected by age-old traditional mustard oil massage, because the two halves of the skull would not fuse till he was three. There was still time to reshape it through the gentle, expressive molding skills of the masseuses who know so well how to improve upon nature’s work. A young woman responded to me in this manner:

“i dont even want to argue w you. pls refrain from peddling pseudoscience on everything under the sun.”

Why do we believe that “science” is somehow wedded to this mechanistic view of the high-tech world, and anything else which does not involve technological apparatuses, Big Pharma, transnational corporations, or Western Latin phrases, is not science? Why has technology become our touchstone of scientific knowledge, not rational and patient observation? Why did we just hand over $9 billion to a tech guy to cure ourselves, when that work should be done by an international consortium of researchers coming from Third World countries where the coronavirus hasn’t spread, and whose traditional science and knowledge have already provided the cure?