In his December 15 royal proclamation, King Mahendra made a number of serious allegations against the BP Koirala government, namely that it was embroiled in partisan politics, encouraged corruption, emboldened anti-national elements, undermined national unity and created a foul political climate based on hollow principles. He said, “Under the shield of democracy, the government used its authority to fulfil partisan interests at the cost of the nation and the people. Instead of honoring the law, this cabinet tried to render the country’s administrative mechanism dysfunctional in the name of making it swift, sharp and able.”

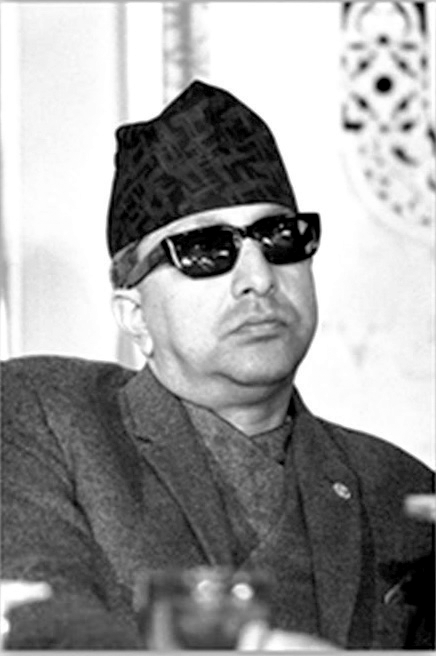

King Mahendra

The king had used just one article in the constitution to bring about the political upheaval. He had abused the ‘emergency powers’ granted to the king in Article 55. Taking a leaf out of Mahendra’s book, King Gyanendra on 1 February 2005 invoked Article 127 of the 1990 Constitution, which gave him the powers to ‘remove difficulties’, in order to seize the reins of government. While Mahendra imposed a ban on political parties, Gyanendra restricted not only political parties but also civil liberties.

The 1959 Constitution was issued under the palace’s guidance and its provisions were favorable to the king. Just one article was enough to render the constitution void. Article 55 had a provision allowing the king to exercise ‘emergency powers’ in case the country faced a serious crisis, an external attack or internal mayhem. Except for some disturbance created by people under the palace’s protection, such conditions did not exist in the country. But the constitution gave the king sole discretionary powers to assess whether the country faced an emergency situation; the government or the parliament had no say on the matter. By abusing the power vested in him by the constitution, King Mahendra staged a coup against the two-third government.

The statute even had a provision allowing the king to take over the authority enjoyed by the parliament and the government. The emergency rule could be extended for up to a year. In fact, it could be continued as long as the king was not satisfied with the state of affairs in the country. Article 56 had a provision whereby the parliament could be suspended if constitutional mechanisms failed, but it could not be dissolved.

A month after the parliament’s dissolution, King Mahendra awarded medals to a number of army and police officers for their help in the coup. Usually medals were given on special occasions, like the monarch’s birthday. But no special occasion was required to honor the aiders and abettors of the coup. Altogether 85 high-level army officials were awarded medals.

In contrast, only 26 police officers were honored, which suggests that the palace did not trust the police force as much as it trusted the army. Five other high-level officers from Singha Durbar and Narayanhiti Palace were given medals for their contribution to the royal conspiracy.

Only after 12 days of usurping the reins of power did Mahendra announce the formation of a new cabinet under his own chairmanship, where he inducted opportunist Congress leaders like Tulsi Giri and Bishwa Bandhu Thapa. Not only were Giri and Thapa the General Secretaries of the Congress, they were believed to be extremely close to BP Koirala. Giri and Thapa were also, respectively, the foreign minister in the Koirala cabinet and the chief whip of the Congress O

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss how the Panchayat system got its name