Two peoples, one way of life

In early 2014 when I was about to leave for Nepal to work as a resident reporter, the head of my Chinese newspaper asked me, “Is everything ready?” “No problem,” I replied. “I grew up at the foot of the mountain, too. The only difference is that the mountains in Nepal are bigger.”

There is an old Chinese saying: ‘Different lands bring up different people’. A similar statement can be traced back to the ancient Greek concept of “geographical determinism”. I have long supported this view. For example, many people in Nepal like spicy food, as do people in southwest China. Sichuan cuisine is known for its spicy taste. The Chinese believe that as the Sichuan mountain area is humid, people there don’t sweat much. They thus eat spicy food to release the excess moisture in their body, which in turn keeps them healthy.

Tens of millions years ago, the ancient Indian continent began to move towards Eurasia, eventually triggering an epic Himalayan orogeny that created the towering Himalayas and the world’s third pole, the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. This powerful force traveled east from the Qinghai-Tibet plateau and was responsible for the development of the Qinling Mountains in central China. When the Yangtze River from the Qinghai-Tibet plateau pushed aside the obstruction of the Qinling Mountains and continued eastward, the cooperation of the Yangtze River and the Qinling Mountains led to the emergence of the famous “three gorges of the Yangtze river”.

My hometown is just beside the three gorges. From this point of view, although more than 2,500 km apart, my hometown and Nepal are neighbors. If viewed from outer space, the whole area affected by the Himalayan orogeny appears as a whole; my hometown is at the eastern gate while Nepalis live at the southern gate.

The smart mountain folks made same bamboo baskets at both the places.

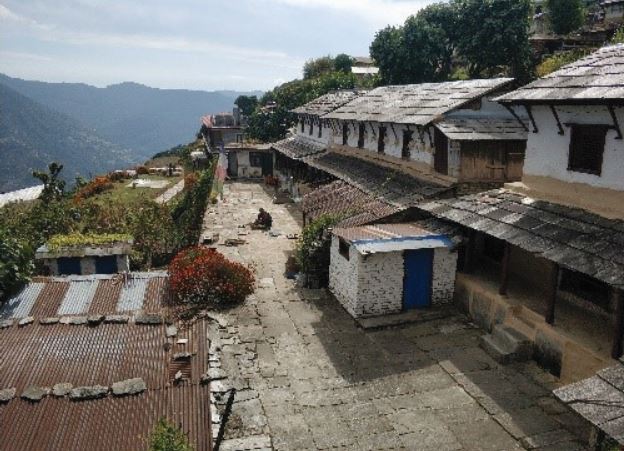

The weather in Nepal is good at this time, so I chose to go trekking in Pokhara. When I came to the Gurung village in the mountains, I suddenly had a feeling of returning home. Really, I thought I could actually see my home.

The above pictures of my hometown (on the left) are all from the internet. Many of them exist only in the vague memory of my childhood. When a person suddenly sees his childhood hometown scenery abroad, he is reduced to tears.

The following part may surprise you: my hometown also has the legend of “yeti”, only we don’t call it “yeti”, but “Ye Ren” (savage). Savage legends have thousands of years of history, and many ancient books also recorded the existence of this mysterious creature. In the 1970s, after the cadres of the local forest farm witnessed the Savage and wrote a detailed eyewitness report to the superior government, the Chinese Academy of Sciences established the “investigation team of mysterious creature” in 1976. With the help of a large number of PLA, it carried out a detailed field research on the relevant forest.

Houses of stone. Yes, 2,500 kilometers apart, the smart mountain folks in Sichuan and Nepal solved the problem of scarce building materials the same way.

Of course, apart from the footprints, feces, hair and reed-woven nests that might have been left by the Savages, there was no strong evidence of their existence, such as a corpse. To this day, this unsolved mystery can still arouse people’s imagination.

Life in the Nepali mountains was enjoyable and I was lucky enough to choose a SIM card that had no signal. I could completely relax from the usual tense life. When there is no Internet, no TV in the cold mountain night, you sit around the stove holding a cup of warm Nepali milk tea: Happiness is that easy.

There is an ancient Chinese poem, which goes like this: “When the bright moon rises in the sky, look up at her. No matter where we are in the world, we will see the same moon and share the same time”. Another ancient Chinese poem says, “If you forget you are a guest in your dream, take this place as your hometown.”

These days I have started considering the whole of Nepal as my hometown.

The author is chief correspondent of the Kathmandu office of Shanghai Wen Hui Daily. He has a Master’s in International Relations

Shared interests define Nepal-China friendship

“There is only friendship and cooperation between China and Nepal, and there are no problems,” Chinese President Xi Jinping said at a state dinner at the Soaltee Hotel on October 12. In today’s international relations, it is not often that two neighbors do not have any problem.

In my view, the fundamental driving force of state-to-state relations today are national interests. That is why China and the US were able to normalize their bilateral relations in the face of an aggressive Soviet Union in the 1970s. It also explains why the US, which always crows about democracy and freedom, views unelected monarchs as its strongest allies in the Middle East. From this point of view, it would be much easier to understand the friendship between China and Nepal.

Perhaps I am not entirely correct. But in my limited understanding, the most important thing for Nepali people is the continuous improvement in their living standards. Of course, other things are also important, but without economic well-being, everything else is a bubble.

Often I have sat alone on the stone steps of the Durbar Square, looking at the great medieval buildings shining at sunset and feeling the past glory of this great country. Looking at those countless wood and stone carvings, I cannot help but wonder about how much manpower and material resources they needed. It may take a skilled carpenter a week to make a beam full of reliefs. But how formidable were the logistical challenges? It perhaps took 1,000 craftsmen to build the entire square, over 100 or more years. The country that created such great buildings must have been powerful.

The world changed overnight when the westerners completed the Industrial Revolution. The unfortunate fact is that the once-mighty Nepal is now one of the least developed countries in the world. Countless scholars have reflected on possible reasons. According to my superficial understanding, a modern country’s fundamental power comes from its industrial production capacity. But due to Nepal’s geographical limitations, it has been unable to have large-scale industries.

Raw materials cannot be easily transported into Nepal, nor can its products be easily exported. Worse, traditional agricultural production has been unable to feed a growing population. As a result, more and more Nepali youths are going abroad for work, instead of building their homeland. Do they not love their country? I don’t think so. But there is nothing wrong with them seeking a better future either. This is a real tragedy.

There is a saying in China: “Build roads before you can get rich.” Without sorting out the challenges of Nepal’s external connections, Nepal’s development problems will not change fundamentally. I may sound a little extreme, but I believe that the so-called “democracy and freedom” cannot solve the fundamental problems of Nepal’s development. In Nepal, there seems to be enough time to quarrel in the parliament and protest on the streets, but not to build roads and other vital infrastructures.

Over the past 40 years, under the CPC leadership, the Chinese people have achieved remarkable success in socialist construction. Many countries are encountering problems in the course of their development. To solve these problems, the Chinese people have also made contributions, in the form of their labor and wisdom. President Xi Jinping has put forward the concept of “Building a community with a shared future for mankind”. China’s goal under the BRI framework of building a “three-dimensional connectivity network across the Himalayas” will help Nepal transform itself from a “land-locked” to a “land-linked” country.

Perhaps some readers will say: “All this talk is propaganda. Isn’t China also acting in its own national interest?” Of course, any country’s foreign policy serves its own interests, and China is no exception. But the point is that China’s interests are aligned with Nepal's.

First, Nepal is an important neighbor of China. So the Chinese want Nepalis to live in a high-quality society rather than only building luxury places in their homeland.

Second, stability and development go hand in hand. On the one hand, development is impossible without a stable social environment. On the other, if the society cannot develop sustainably, people’s living standards cannot be improved and social stability is undermined. For example, Nepal has had 10 governments in the past 10 years. As an important neighbor, Nepal’s prosperity is good for China. I cannot think of any counterexamples. China therefore hopes it can help Nepal realize the goal of “prosperous Nepal, happy Nepalis”.

Third, and more realistically, if Nepal falls into the trap of poverty and unrest, China’s national interests, especially its national security, will also be threatened. Poverty and unrest will weaken Nepal’s sovereignty and lead to more foreign involvement. Perhaps some countries will use Nepal’s territory against China. Of course, no country would publicly admit to doing any of these, but the possibility cannot be ruled out. If helping Nepal become stable and developed can reduce this possibility, why not?

China-Nepal relations are rich and multi-dimensional. What I want to emphasize here though is that it is not only the members of the CPC and the NCP who are comrades, but also the people of China and Nepal. This is the foundation of China-Nepal relations, rooted in protecting shared national interests. Nepal-China friendship, Jindabad!

The author is chief correspondent of the Kathmandu office of Shanghai Wen Hui Daily. He has a Master’s in International Relations

Comrades to enemies

Continued from the previous column…

In the early days of their corporation, both the CPC and the KMT were sincere. Mao Zedong, for example, was secretary of the central bureau of the CPC and acting head of the KMT’s central propaganda department. In order to build a strong revolutionary army, the KMT established the Whampoa military academy in 1924 with the help of the CPC. Zhou Enlai, the newly returned leader of the European branch of the CPC, served as a political instructor in Whampoa, teaching a course in political economy. As the political basis for opposing imperialism and warlordism was the same, members of the CPC and the KMT called each other comrades.

The cooperation between the CPC and the KMT created a great revolutionary power. In 1925, the revolutionary government of Guangzhou defeated the warlords of Guangdong province, making Guangdong the new base of revolutionary forces. In 1926, the 100,000 revolutionary troops led by the KMT and CPC began a war to eliminate warlords in the north. Starting from southern China, they liberated large areas of central and northern China in nine months. In 1927, the revolutionary army took over the concession of the British colonists in Hubei province. In this process, the CPC mobilized the masses to provide logistics to the revolutionary army. The underground organization of CPC also organized labor unions in warlord-ruled areas to launch labor movements in support of the revolutionary army.

But the seed of instability had sprouted years earlier. Sun Yat-sen died of liver cancer in Beijing in March 1925. After his death, infighting started in the KMT. The increasingly close relationship between the CPC and the left wing of the KMT aroused the resentment of the KMT’s right wing. At the same time, ideological differences between the CPC and the KMT began to emerge.

The KMT was a bourgeois party, representing the interests of the urban bourgeoisie and the rural landlords. Although the KMT and the CPC shared the same political desire to drive away imperialist forces and warlords, the communist party still needed to safeguard the interests of the working class in the cities and carry out land ownership reform in the countryside. As a result, the gap between the KMT and the CPC widened.

Between April and July 1927, the KMT rightists, represented by Chiang Kai-shek and Wang Ching-wei, launched two sudden campaigns to kill communists. Within a few months, tens of thousands of communist party members and pro-communist revolutionaries were killed or persecuted. The cooperation between the KMT and the CPC broke down completely.

The bloody slaughter taught the communists that they must have a revolutionary army of their own. On 1 August, 1927, Zhou Enlai launched an uprising in Nanchang, the capital of Jiangxi province. On August 7, the central committee of CPC held an emergency meeting, at which Mao proposed that “the power to rule comes from guns”. On 9 September, 1927, Mao led the workers’ and peasants’ uprising in border areas of Hunan and Jiangxi provinces. On September 29, Mao established the leadership of the CPC over the army. On October 27, his troops arrived at Jing Gang mountain, creating the first revolutionary base under the CPC leadership. After that, in January 1928, Zhu De (later commander-in-chief of the People’s Liberation Army) launched a peasant uprising in southern Hunan province. In April 1928, the troops of southern Hunan uprising and Nanchang uprising arrived at the Jing Gang mountain base.

From October 1927 to January 1930, Mao wrote three articles—“Why can China’s red regime exist?”, “Struggle in Jing gang mountain” and “A single spark can start a prairie fire”—marking the starting of the theory of the revolutionary road. The goal was for the countryside to encircle the city.

Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-shek gradually gained the upper hand in the internal struggles of the KMT. Zhang Zuolin, the leader of China’s most powerful military warlord, was assassinated by the Japanese in June 1928 after rejecting Japanese demands to expand their colonial interests in northeast China. Zhang Xueliang, Zhang Zuolin’s son, was extremely angry and at the end of 1928 he declared northeast China subordinate to the nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek. From then on, Chiang Kai-shek ostensibly completed the reunification of China.

The CPC and the KMT (which later went on to rule Taiwan) completed their journey from being comrades to enemies.

Birth of modern China

The tumbling Yangtze River, towards the east it runs. The splashing waves, like moments in history, heroes are made and then are gone.

—Opening poem of the Chinese novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms

It is a miracle that the Nepali people were able to protect their country’s independence during the colonial era after a heroic fight. China was not so lucky.

After colonizing India, in order to sell opium to China, Britain opened the door of China with cannons in 1840. Then, imperialist colonialists started coming to China one by one, starting one aggressive war after another, and signing one unequal treaty after another with China. In 1900, China’s shaky Qing government was defeated by a coalition of Britain, France, the US, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, Japan and Italy. From then on, the Qing government completely surrendered to imperialism and China came to the brink of collapse.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th

century, China was on the verge of collapse because of the assaults of

imperialism.

Great nations in times of crisis produce great men, such as Turkey’s Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938), India’s Mahatma Gandhi (1969-1948) and China’s Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925). In 1911, some soldiers of the Qing army with revolutionary ideas launched an uprising in Wuhan. Soon, Sun Yat-sen, the bourgeois revolutionary leader, returned to China and became the provisional President of the Republic of China. In this year, Mao Zedong, an 18-year-old student, became a revolutionary army soldier in his native Hunan province. Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-shek, 23, would be a mid-level commander of the Shanghai revolutionary army.

However, northern China was still under the control of the Qing dynasty. The most effective troops of the Qing dynasty under Yuan Shikai were fighting the revolutionary army. Yuan was an ambitious man. Politically ambitious, he let the war go on and on. During this period, Yuan asked the revolutionaries to agree to his presidency with military pressure, while crying to the five-year-old Qing emperor Pu Yi that the revolutionary army was too strong, and that if the emperor did not abdicate, the imperial family might be slaughtered in the end.

Although the revolutionaries hated Yuan, Sun decided to make Yuan President for the sake of China’s unification. After the Qing emperor abdicated as President, Yuan quickly revealed his own ambitions, and in 1915 proclaimed himself emperor of the so-called Chinese empire. Six month later, Yuan died. After his death, China entered a period of warlord division.

Then, in 1917, the tsarist rule in Russia came to an end in an armed uprising led by Russian communists. Some Chinese intellectuals saw another way to save the country—communism—a different path from the bourgeois revolution. In 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference after World War I, the colonial interests of the defeated Germany in China’s Shandong province was transferred to Japan, even though China was among the victors. On May 4, the Chinese communists led a mass student demonstration in Beijing and the Chinese communists stepped onto a new stage of history.

Later, communist groups were set up all over China and even among overseas Chinese. In 1921, 13 delegates from across the country held a secret meeting in Shanghai, marking the official founding of the Communist Party of China (CPC). Mao Zedong, 28, attended the meeting as the representative of

Hunan province.

At the same time, Sun Yat-sen established a military government in Guangzhou, hoping to unite with warlords in the southern provinces to eliminate northern warlords and complete the reunification of China. But his efforts failed because of lack of unity. After the success of the Russian October Revolution, Sun hoped to learn from then successful experience of the Russian revolution and to get

Russian assistance to build up his own military force. In 1919, Sun reorganized his

revolutionary organization as the Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang (KMT).

In the 1920s, with the backing of different western colonial powers, Chinese warlords attacked each other year by year. It had become the common aspiration of the whole Chinese people to drive out the colonialists and end the warlordism. With their political foundations against colonialism and warlordism, both CPC and KMT recognized the need for co-operation. In June 1923, the third national congress of the CPC established the policy of establishing a revolutionary united front with the KMT. In January 1924, the first national congress of the KMT formulated a policy of cooperation with the Soviet Union and CPC.

Two of China’s most important political forces in the first half of the 20th century—the KMT, which represented the bourgeoisie, and the CPC, which represented the

proletariat—began to cooperate to save the country from collapse.

(To be continued...)

The watery political traditions of China

Days of heavy rainfall have resulted in severe flooding in Nepal’s southern plains. As of July 16, the floods left more than 78 people dead and countless families displaced. As a Chinese journalist working in Kathmandu, I feel the same sadness as the Nepali people. I spent my childhood by the Yangtze River; I know the horrors of floods.

My birthday is in the summer, and I still remember that particular one in 1998. That night, at 10 o’ clock, my parents were at home to celebrate. As I was about to blow out the birthday candles, my father’s beeper went off. My father said, “Sorry, a huge flood is coming. All civil servants of the city must gather now and go to check the levees and prepare for safe crossing of the flood peak.” The next day, when I came to the levees of my hometown, I saw that they had been raised by one meter with the help of sandbags overnight, and the swift current of Yangtze flowed downstream just below my feet.

During that flood season in 1998, there were eight flood peaks in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River. After they converged with the floods of middle and lower reaches, the basin saw its biggest flooding since 1954. At Wuhan, a megalopolis of 10 million people, 400 kilometers downstream from my hometown, the runoff reached 71,100 cubic meters per second. To put it another way, the flooding at that time could form one Phewa Lake every 10 minutes. If the levees burst, the densely populated Jianghan plain would become a vast ocean.

At this critical moment, the central government immediately mobilized hundreds of thousands of PLA soldiers and armed police to fight floods. Under the strong leadership of the party and the government, and unremitting efforts of the army, the Chinese people achieved a great victory against the floods in 1998.

Water is the source of life, nurturing civilizations. But water is temperamental too. When cold air from Siberia meets warm, moist air from the Pacific, there is seasonal rainfall over China. If these two streams of air are evenly matched in one place for a long time, rain will continue to fall, followed by flooding, and drought. Therefore, as a large agricultural country, fighting floods and drought has been one of the main tasks of China’s internal affairs for thousands of years.

China’s diplomacy and military struggles have also traditionally been about water. The 15-inch isotropic line divides the East Asian landmass between farming and nomad areas. If the cold air from Siberia is too strong, the rainfall areas on the Chinese mainland move south. The northern nomads lived in cold and dry areas, and they could have invaded agricultural areas in the south to survive.

So organizing the whole country’s power to prevent the invasion of northern nomads was one of the most important parts of the Chinese government’s diplomatic and military struggles for thousands of years. The Great Wall was thus built to keep the nomads at bay.

Whether it is to overcome natural disasters or resist aggression, huge manpower, material and financial resources needed to be mobilized in China. In order to maintain such a large country and ensure the continuation of its civilization, a strong central government had become a historical necessity.

There are many legends of the floods from ancient times, such as the story of Noah’s ark in the Bible and of Yu the Great, the head of a Chinese tribal alliance, who controlled floods about 4,000 years ago. In Yu’s time, China’s Yellow River basin flooded every year, and Shun, the leader of the tribal alliance, appointed Yu to take charge of flood control. Yu commanded all the tribes, and after 20 years of unremitting efforts, successfully diverted annual floods to areas not harmful to human beings. Through the flood-fighting process, Yu gradually united the tribes and after Shun died, eventually founded China’s first dynasty, the Xia. From that time, ancient China began to evolve from a tribal alliance state into a state with strong central government.

Some historians say water shaped China’s traditional politics. In fact, this form of politics with a strong central government plays a positive role to this day. In the 1960s, China developed atomic and hydrogen bombs and successfully launched man-made satellites despite its weak economy and poor technological strength. With the help of modern technology, this political tradition has played a great role in fighting floods also.

In 2006, the Three Gorges project, the world’s largest dam, was completed. In addition to helping with power generation and shipping, the project has a total water storage capacity of 133.2 billion cubic meters. If the floods of 1998 were to recur, the threat to people in the Yangtze basin will be greatly reduced. The 200-billion-yuan construction cost, relocating a million people in the reservoir area, the collective support of China’s scientific and engineering institutions—all these efforts called for a strong central government.

In Elements of the Philosophy of Right, German philosopher Hegel states: ‘What is reasonable is real; that which is real is reasonable’. The current state of each country is the result of its living environment, historical tradition and other factors. Because of this, the world is colorful and full of charm.

The author is chief correspondent of the Kathmandu office of Shanghai Wen Hui Daily. He has a Masters in international relations

Peking roast duck in Kathmandu

An old Chinese saying goes, “Different lands and waters nurture different people.” As China’s territory extends from the cold zone to the tropics, from the Pacific Ocean to the Himalayas and the Gobi Desert, over thousands of years Chinese food has naturally been as varied. According to the simplest method, the food of just the Han Chinese can be divided into four sub-systems: Sichuan cuisine (southwest region), Cantonese cuisine (southern), Huaiyang cuisine (southeast), and Lu cuisine (north). The Chinese love for food and loyalty to the taste of their hometown makes them sensitive to subtle differences in taste. “Chinese stomach” is a term used to describe the physiological reaction of a Chinese who has been deprived of Chinese food for a long time. Its main manifestations are bad temper, lack of concentration, and interest in nothing. My wife and I are both Han Chinese. If we analyze the reasons for our quarrels at home, the argument about “Sichuan or Lu food” is always Number 1.

I arrived in Kathmandu at a time the Chinese were waging a national debate on social media about whether to add sugar or salt sauce to Doufunao (a kind of very soft tofu). In this, my first long-term job abroad, I found the Chinese food has grown new branches and flowers abroad. In Kathmandu, you can eat Southeast Asian Chinese food, you can eat Indian Calcutta Chinese food, and you can even eat Chinese steamed buns (Dai Po) that may have been brought to Nepal from Southwest China, Myanmar and the southern foothills of the Himalayas. When the Chinese people go to these overseas Chinese restaurants, they have indescribable experiences that are both familiar but also different.

The Big Bang Theory, an American TV series, loved by many Chinese viewers, has takeaway scenes from a Chinese restaurant. After research by curious viewers, this Chinese restaurant has become one of the most popular in the US. When Chinese netizens went to the US to try the food from this Chinese restaurant, most of them were surprised that the Chinese food here was so different to the food they grew up with.

The same is true in Kathmandu. Peking roast duck is a famous delicacy in Beijing. The three most important parts of the dish are the roast duck, the semi-transparent pancake used to wrap the duck meat, and the sweet bean sauce. Once I ordered Peking roast duck at a Chinese restaurant in Kathmandu owned by an overseas Chinese. When the dish was brought, I was shocked: the duck was not roasted on firewood, the pancake was thick and stiff, and even the sauce was cranberry sauce. The restaurant manager politely asked me how I felt about the dish. My reply embarrassed him.

Not just Chinese food. When traveling to unfamiliar places in China, I tend to choose well-known chain restaurants because I think they have good “quality control” and consistent prices. When I came to Kathmandu, my principle was broken, because even at international fast food chains in Kathmandu, the chicken nuggets are more spicy and saltier than what you get from the same chains in Beijing!

Many Chinese restaurants in Kathmandu are not authentic Chinese. Yes, but so what? What is authentic Chinese food? Chinese civilization has a 5,000-year history. Do we eat the same food as the ancients? Sichuan cuisine is famous for its spicy flavor, but remember that chilies, native to South America, didn’t go global until after the great age of sailing.

I used to be able to argue indefinitely with dissenters even over a small issue. In recent years, I suddenly feel there are no right or wrong answers to many things. What is the best? What is suitable for you is the best, and what is suitable for the local people is the right choice. Why do I have this idea? Maybe I’m getting old.

There is a famous dish in Sichuan cuisine—boiled meat slices. Traditionally, the main ingredients have been beef or fish. Since I respect the customs and religious beliefs of the local people, I never order this dish when I invite my Nepali friends to dinner. One day I was having dinner with Nepali friends at a Chinese restaurant. The head chef there was happy to tell me that, through experiments, they had succeeded in making boiled meat slices from pork. After the chef’s introduction, my Nepali friends tried the pork version. They loved it, and I thought it was just as delicious as the boiled slices of the more traditional stuff.

You see, that’s a good example of how different lands and waters nurture different Chinese food. Any culture that can continuously evolve and adapt to the objective environment is a culture with vitality. The Chinese food is no exception. Only thus can a civilization preserve the essence of its culture and make it a bridge of understanding with other civilizations.

I should get going now. My wife is cooking tonight. I better start cleaning the vegetables if I want good food.

The author is chief correspondent of the Kathmandu office of Shanghai Wen Hui Daily. He has a Masters in international relations.